Growing up, Cuba was an influential part of my life. My father and grandparents left the country in 1967, and my grandparents always longed to return home, describing Cuba with great nostalgia. It wasn’t until I grew older, though, that I realized how little they mentioned the revolution itself or its aftermath. They spoke of Cuba with love and Fidel with anger, but they swept past the bad times and painted a picture of an island of dreams.

The tumultuous parts of their life in Cuba were a mystery to me, one I uncovered while writing “Next Year in Havana”.

The strong emotions Cuba conjured within my family inspired me to write about the experience of exile from the perspective of two generations. In the summer of 2016, we planned a family reunion in Cuba, and in the course of organizing the trip, my grandfather became very upset. His pain at the idea of returning to Cuba in its current iteration introduced a conversation within our family about the weight of exile. My journey working on the novel closely mirrored Marisol’s experience as I learned more about my family’s life in Cuba, particularly in the revolution’s aftermath, and also as I examined my own Cuban identity.

Writing and researching Next Year in Havana was eye opening and gave me a more nuanced look at the revolution, and at a time when I felt the loss of my grandmother keenly, it gave me a new connection to our history and a greater appreciation for my family’s courage and strength.

There were always hints at the darker side of my family’s life in Cuba.

My grandfather could never waste food. He didn’t believe in throwing anything away, and it wasn’t until I was older that I understood it was because he knew what it was for food to be scarce during the eight years he lived under Fidel’s regime. There’s a story in the book that Luis recounts to Marisol, of life after the revolution when his family was faced with a food shortage and were given meat from friends in the country that they took back to Havana in the trunk of their car. The car broke down and his family was terrified as others started helping them get the car running again that the meat would be found and they would be imprisoned for violating the rationing system. That incident happened to my father and grandparents before they left Cuba. I learned this story when I was working on Next Year in Havana, and I was struck by how desperate things must have been at that time.

“I saw the apartment my family lived in when they first arrived in the United States as refugees, and it hit me then how much bravery and sacrifice went in to giving me the life I live today.”

I always knew my grandfather was sent to the countryside for a year—away from his wife and son—as punishment for asking the government for permission to leave Cuba. Before I began working on the book, I’m embarrassed to admit, I didn’t fully understand what that meant. I thought he was just practicing medicine outside Havana. I didn’t comprehend that he was part of a larger group of many Cubans who were sent to do hard labor in the country as punishment, frequently under harsh and dangerous conditions. In the course of speaking about the book, I met others whose families had similar experiences, and I began to understand even more what so many families suffered during that time period—and the lengths they went to in order to secure a better future for their children and grandchildren.

My legacy is a proud one, and working on this book really highlighted the importance of that legacy for me. My grandmother was one of the most influential people in my life, and when she passed away over a decade ago, there was a hole in my heart. Writing Next Year in Havana made me feel as though she was with me as I traversed the Cuba she loved through her stories and memories.

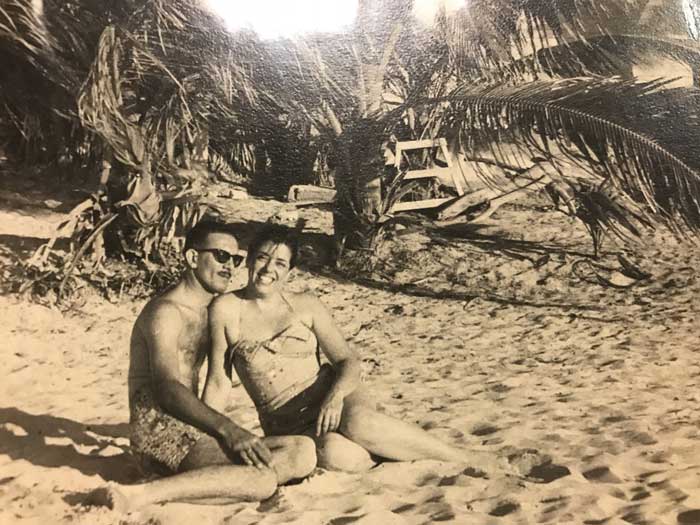

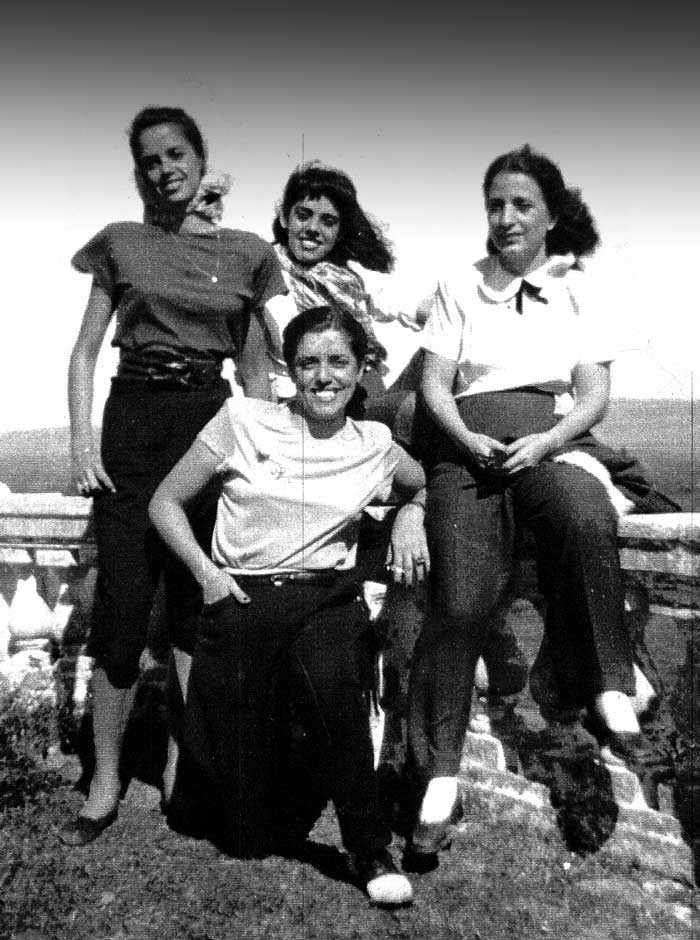

My grandmother was forty years old, had polio, and was pregnant with her only child—my father—when Fidel came to power in 1959. I can’t imagine how terrifying it must have been to go through such turmoil and uncertainty in such a pivotal moment in her life, and following her footsteps in the book only made me admire her grace and fearlessness even more. She taught me what it meant to be a Cuban woman, and I loved celebrating that spirit in Elisa and her sisters.

I recently had the opportunity to go back to Miami with my father and grandfather. I saw the apartment my family lived in for a year when they first arrived in the United States as refugees, and it hit me then how much bravery and sacrifice went in to giving me the life I live today. My grandparents left Cuba with little more than a suitcase and their little boy in tow. They buried their valuables, their most cherished possessions, in a box in the backyard of their home, thinking one day they would return. They crossed an ocean, arrived in a foreign country where they didn’t speak the language, during what should have been the golden years of their lives, and with the help of friends and family, they started over completely. They built a life here and they thrived, always waiting, always hoping that one day they would return.

My family’s story really isn’t that uncommon. It’s the story of so many families who have been forced into exile, who have had to leave their home when violence and turmoil made it impossible to stay. My family is part of a powerful community of families who have passed on their history, traditions, and hope to the next generations. I have never been prouder to be Cuban-American than I am now.