A Cuban Girl’s Guide to Tea and Tomorrow grew from many places, some unexpected––like a corn field in the middle of Orlando, Florida. My tío Oscar grew corn in a plot that spanned the width of his backyard. As a little girl, I ran the perimeter in the ripe humidity. Inside, my tías cooked with my mother. This was the home where we gathered, celebrating our annual visit from California, or a wedding, or a new baby, or simply the fact that we were together again.

I am the youngest of many cousins. My cheeks were peppered with besitos as I was passed from knee to knee and set upon a kitchen stool to watch and listen. More relatives would pour in from other homes. A domino match might erupt amidst the twist and flurry of a portable fan and the drone of a televised baseball game. My older cousins traded stories and jokes. As a child, I thought these were magic rooms, small in square footage, but as enchanted as the corn fluttering green and winged outside the patio slider. Somehow, they held us all.

From the picked and dried corn Tío grew, Tía Vergarina would grind bags of masa for tamales. While she and her sisters in law prepared them and other wondrous offerings, I was sometimes allowed a glass of Coke with a lime wedge hooked onto the rim. I was always handed a steaming empanada stuffed with ground beef picadillo, or a spoonful of mermelada de mango. From this spot and in many Orlando and Miami homes, I began to learn how life worked. The ingredients forming good relationships, and the ones that could turn an entire pot bitter with a mere teaspoon. How love grew and how it sometimes dried and withered at its root.

At these meals over years and summers, a new fiancé or spouse would be seated at my tíos’ table. Fed and fawned over and stuffed to bursting. This was my family’s welcome anthem. You are ours, now. On these occasions, Oscar would roast an entire pig in front of his corn field in a custom grill he built. They served platters of lechón asado and bowls of congrí (black beans mixed with white rice and plenty of garlic.) Trays of home grown avocado and pillowy empanadas. Waiting on a sideboard was flan in a puddle of golden caramel. Here, they spoke fast, my primos and tíos. I caught every few words in the Cuban Spanish that is both lazed and insouciantly neglectful of ending consonants, and charged with a relentless thoroughbred gait. I managed to understand their truths and lessons and joys. Later, I would learn this was how they really fed me.

“From this spot, I began to learn how life worked… How love grew and how it sometimes dried and withered at its root.”

But with all they fed me, the tamales were a highlight.

Growing up in San Diego, I’d had wonderful Mexican style tamales. Tía’s were different. The corn Tío grew and processed so expertly, when rolled around pork filling and steamed, came out a bold, almost saffron yellow. I’ve still never seen it replicated in tamale form. No crayon claiming to be “maize” in my jumbo box was ever this color, either. I learned the reason: the corn from Tío’s backyard was not from here. Not from Florida, or anywhere in the United States. Then again, neither was my family.

My tíos were born and raised on a small farm in Yaguaramas, Cuba. My mother, also the youngest, was the first to leave Cuba as an exchange student shortly before Castro assumed power. Her many brothers and sisters and their families followed as they could. When Tío Oscar came to Florida, he brought a bag of corn kernels from the family farm among his meager possessions. He settled and planted our Cuban corn that had started from a root and seed more than a century ago. Family members, seeds––both had been replanted here to grow and feed us for generations.

I was always the youngest, but I grew too. And one summer, it was my turn to travel with my husband and our four-year-old boy and baby girl to that Orlando home for dinner. My son ran the perimeter of Tío’s corn plot. My little girl’s cheeks were peppered with besitos. She was passed from knee to knee and lifted high to watch my tías prepare the lechón asado, and the flan, and the tamales. My husband was seated at the table, fawned over, fed, and stuffed to bursting. You are ours, now.

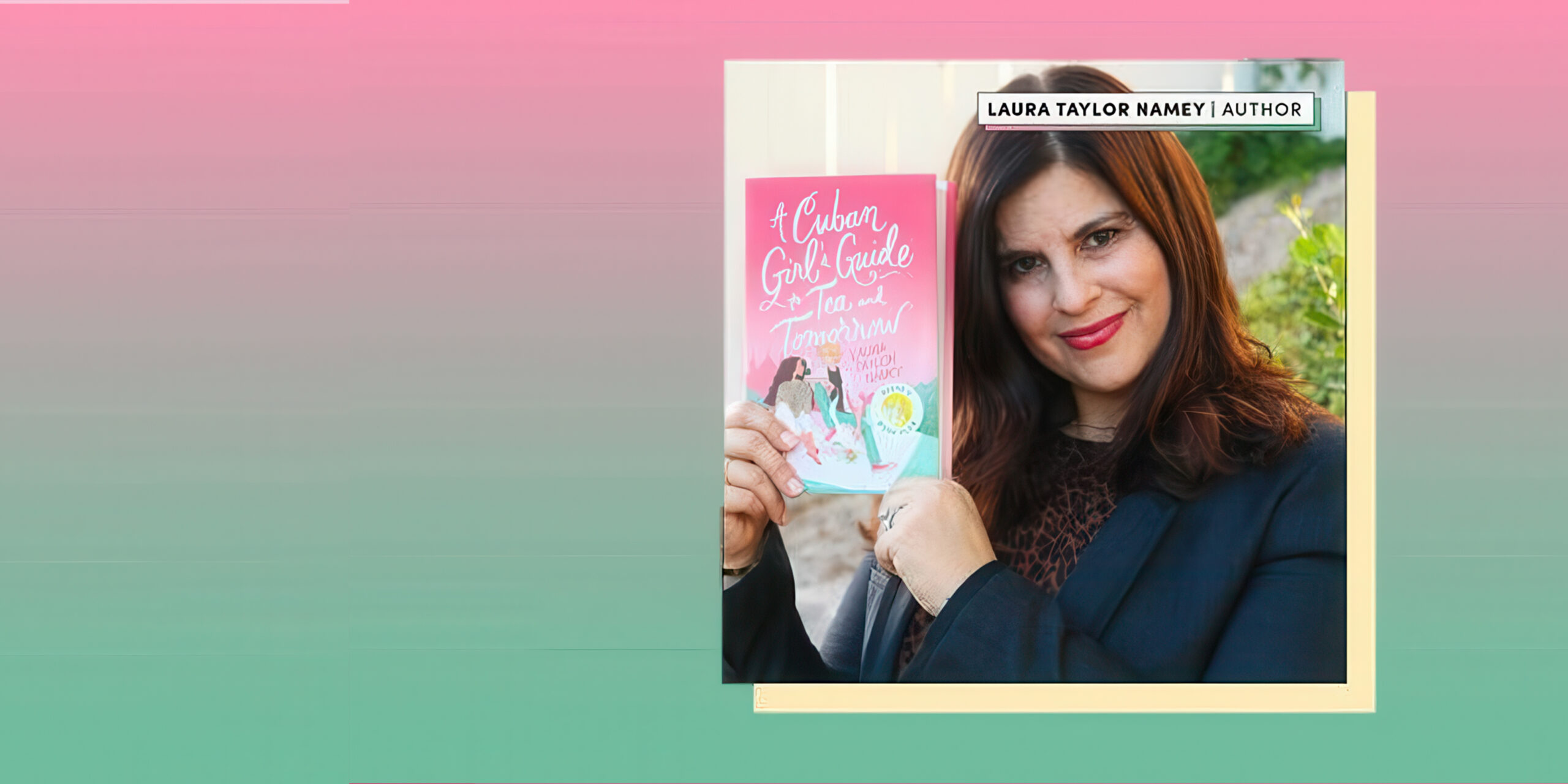

Today, that table is missing some of its beloved souls. If our Cuban corn will thrive, we––my cousins, their children––must tend it. But I chose to grow us in another way. I wrote a book called A Cuban Girl’s Guide to Tea and Tomorrow where Lila Reyes runs the perimeter of her tío’s corn plot as a girl. When she is fifteen, she has her first kiss there, hidden behind the stalks from the watchful eyes of her tías. Our story, our people live on in these words. They grow between pages that are sized to fit between a reader’s hands. Small, yes, but somehow they hold us all.