When I was sixteen, I was runner up in a national gospel singing competition in England called J-Factor. The winner got a flight to America to record a single. The runner up got the experience and what an experience it was. In front of an audience of a thousand people, I sang two covers and an original composition. It took me a month to come off the high. In the aftermath of the show, I was scouted by an independent record label but I never signed anything. I was too young and too daunted by the fast pace everything was suddenly moving at.

I also had other interests. At seventeen, I began the novel that would become The Spider King’s Daughter. At eighteen, I found a literary agent and at nineteen, I signed a book deal with my first publisher. I wasn’t yet twenty and I had set off on my writing career, leaving music behind.

Except of course, I never left my music behind. I just stopped singing in public. Singing didn’t seem to gel with my new ‘image’ as a writer. Sometimes if you’re known for one thing, it seems an insurmountable difficulty to put yourself forward as another thing. Jack of all trades, master of none, etcetera.

Until one day, I gave myself a good mental shake. Who told you that you could only be one thing? In the words of the poet Anjola Adedayo, “Your name is not Jack. You can be master of as many trades as you like.” I started singing at every public appearance. A short video of me singing on the BBC World Service went viral on Instagram.

A friend of mine noticed the change and said to me, “Why don’t you release a single with your next novel?” It seemed a ludicrous idea. Who’d ever heard of a soundtrack for a novel?

“That’s the point,” he said. “It would be something new.”

I thought about it but still dismissed the idea. I didn’t have the time to execute it properly. Although I had a notebook full of songs, none of them quite fit the themes of SANKOFA. And writing an original song would take too long.

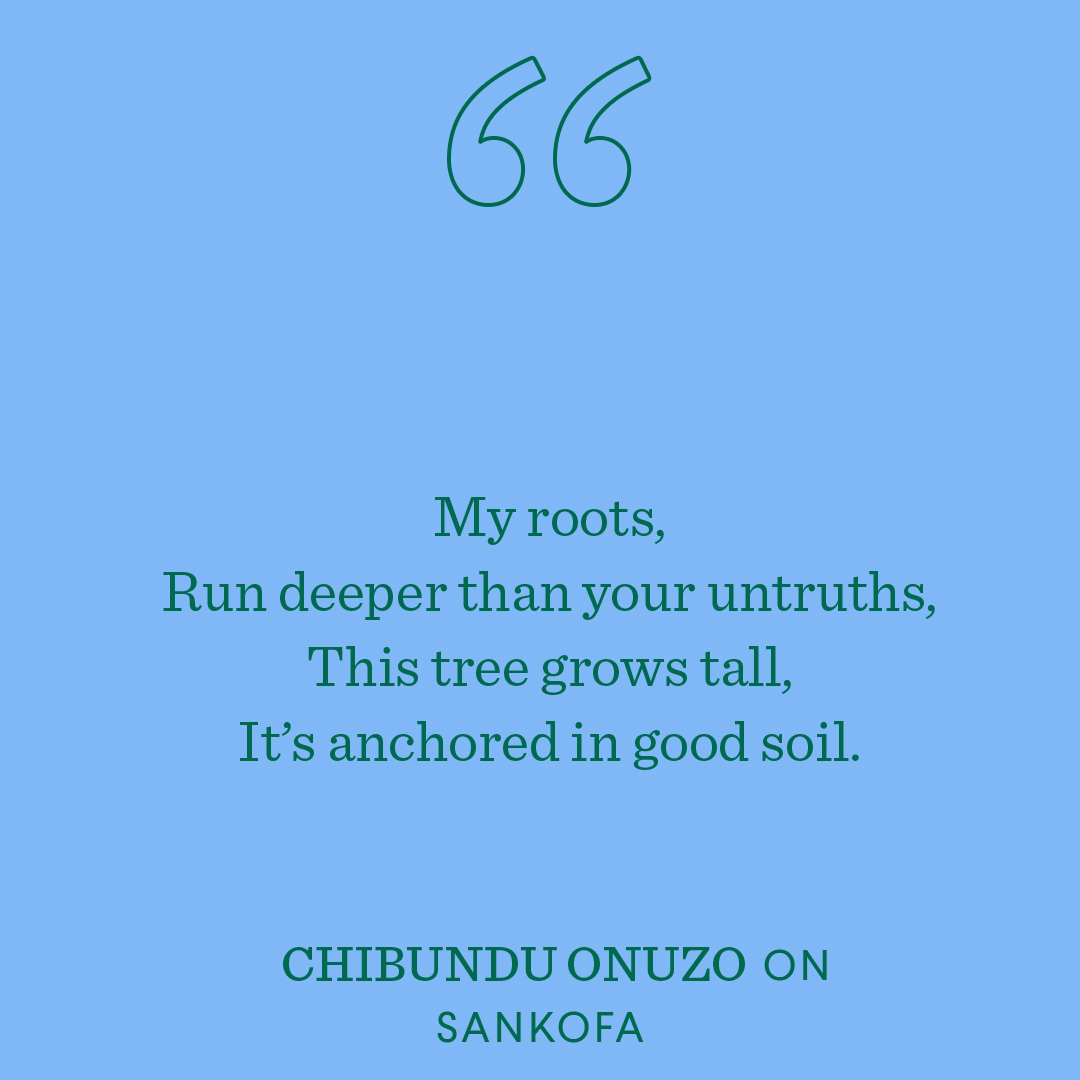

And then a global pandemic struck and my calendar cleared up. Stuck at home, I found myself sitting at the piano messing about with chords. The opening lines of Good Soil came to me:

The first verse continued to tell a story about identity and ancestry and heritage, all ideas I explore in SANKOFA. Anna, my main character, is searching for her father and in doing so, is searching for her roots. By the time I reached the chorus, I was declaiming:

I approached my friend Féz to produce the track. He’s a whizz on the drums but also has an excellent ear for arrangement. Once the track was recorded, I just knew I had to make a music video. I had a vision of celebrating black people in all our multifaceted excellence. The Olympic gold medallist Christine Ohuruogu appears in the video but so do Lanre and Tara Gbolade, architects and founders of Gbolade Design Studio. The comedian and radio DJ Eddie Kadi makes a cameo but so do Oge Ilozue, Yinka Gbolahan and Emma Amoafo, all doctors on the frontline during the pandemic.

To make the video, I called every single favour and I mean EVERY SINGLE FAVOUR. The Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery in London Bridge kindly gave us permission to shoot on their premises with art by Gerald Chukwuma in the background. Director, Joseph Landreth and Director of Photography Joe Gubb, brought my vision to life in glorious technicolour. And my family, friends and colleagues rallied round to star in the video.

The response to Good Soil has been overwhelmingly positive. To think that I almost stopped singing in public because I felt I could only be one thing. To think I almost didn’t write Good Soil because novel don’t have soundtracks. Well now they do.