At the age of three, in 2005, our daughter Gracie received a bone marrow transplant at the Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Program at Duke Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina. On this unit, every patient is assigned a ‘primary nurse’; it was our great luck to be assigned to Bobbie Caraher. Bobbie made the most frightening time of our lives immeasurably better with her unique dedication to working bedside, where her humor, experienced eye and genuine human warmth bring healing, in the truest sense, to all the families under her care.

Before beginning her 15-year career at Duke, Bobbie worked for multiple refugee organizations, nursing some the world’s most vulnerable populations, including in Malawi, St. Lucia, Sudan, Vietnam, Thailand and Pakistan.

Heather Harpham: Bobbie, you were so special to our family. With most doctors or nurses, Gracie was truly fearful. She would literally growl when they entered the room. But you disarmed her. She showed you the first spontaneous gesture of affection I ever saw her offer medical staff. On our second or third day on the unit, when you entered the room, she opened her arms to you.

Bobbie Caraher: Ah, Gracie. Sometimes patients or even parents are scared and that can make them lash out. And we have to understand that. It’s not right if a little kid tries to hit you or a parent is yelling. We can’t allow that. But, we’ve got to try to understand where their pain or anger is coming from.

HH: How did you decide to become a nurse?

BC: I’d been living in Laguna Beach, California, in my 20s, with my sister and some friends. Having a good time. And I decided I needed to go back to school, for something that would help people. But I couldn’t decide what to study so I thought, I’ll just leave it up to fate.

HH: If I remember right, you opened up the course catalog randomly and decided you’d study whatever subject was on the page you opened to.

BC: It was a little more dramatic. I threw the book up in the air actually, I remember I threw it right up in the air; it was going to hit my friend.

HH: And it landed on…

BC: The nursing program. It was right there.

HH: What year would that have been?

BC: 1974 or 75, because I graduated in ’79.

HH: After school, how did you decide what kind of nursing you wanted to do?

BC: There’s a really nice hospital called Children’s Hospital of Orange County, in Anaheim. The first day I visited (on rotation), I just knew that it was where I wanted to work. There was no other place. It was like, “This is where I’m going.” I went and applied and was hired right away. And that was it.

HH: You once said of nursing, “You know what to do by looking at people’s faces…”

BC: Nowadays, when people are looking at other people, they are often not really looking. We’re all thinking of five million other things, or not really listening to what others are saying. To be a good nurse, you have to slow down and be aware of what patients are saying and what they really need. With children, it’s especially easy to see what they need because they don’t have so many things blocking them. You can look at a two-year-old and there’s just clearness; they are really looking back at you. It’s that simple. That’s why I enjoy working with kids.

“I tell the young nurses on our unit, “Hold your pain close. Your suffering can turn into happiness. Instead of pushing it away, hold your pain close, like you would a puppy that’s crying, until it can become a part of you.”

HH: Was there anything you learned over the long span of time you worked with refugees and displaced people in so many countries?

BC: Working with refugees is a very particular kind of care. You think you know what they’ve gone through until you actually meet someone face to face. You can read a book about the refugee experience but, boy, when you meet somebody whose whole family is gone and they don’t know their future and they are locked up in a camp and if they go home they’ll be killed and no one wants to send them to America or Australia… It’s just horrible to see someone going through that day by day.

And also, people think that everyone’s so different, but they are not, at all. They want to have children who are happy and healthy, who can learn to read and write. Who have food and clean water. That’s all anybody wants. If their child gets sick, they are just as devastated as anyone else. Or if their child dies. Like everybody is the same, really. They might talk differently or eat different foods or wear different clothes. But that’s about it. These days it’s “America, America!” But this is global, this is the earth. We’re all one. There’s so much to be learned from other people and other cultures.

HH: Can you talk about how the qualities that we find in spiritual life – presence, mindfulness – relate to the nursing you do?

BC: Oh, gosh, I’m not sure. With the kids, no matter how young they are, I let them do their own thing if it’s not going to hurt them. A lot of nurses aren’t like that. They feel they have to perform certain task immediately, even if the parents ask, “Could you wait a half an hour?” Nurses can be like that because they want to give patients the care that they need; it’s not that they like being mean or anything. But I feel that sometimes things work out better if you can listen to what the parent or mom or dad or caregiver wants to do. I practice more like that. And it always works out the best way. It always does. There’s never a time I could say, gee I wish I would have listened to myself first. It’s always like gee I’m sure glad I listened to the mom and dad.

HH: But Bobbie, I remember you — gently, lovingly, but firmly — urging us to get Gracie onto morphine. So that was an instance where you did know best, and you pushed the parents.

BC: Oh yes yes. I’m thinking of things like baths and walking and things like that. I can tell when someone’s in pain and I think I was looking at Gracie’s eyes. And I was aware of her pain. So I actually was listening to her, the patient. I remember that. I think I said, “Heather, just look in her eyes.” I think I said that to you. There was no sparkle, there was nothing. There was just suffering.

HH: And, at the same time it was hard for me to acknowledge because she was not saying she was in pain.

BC: A lot of times patients don’t because the kind of pain that they’re in – the older kids will tell you this – they’ve never had that kind of pain before. It’s not a pain in the head or the foot or like you’ve fallen down. It’s this horrible pain all over that can’t be described. That’s why younger kids can’t explain it to us. And that’s why we have to be looking, watching, really seeing them. The parents might say, “They’re not in pain, they’re so quiet.” But they just don’t have the energy or the words to explain their pain. But I am looking. I’m looking at the child, his face, his eyes, and I can see that they are suffering. If I’m looking, I’m aware of that.

HH: With Gracie, I was so afraid to start the morphine drip, and I had my reasons, though they weren’t good ones. And you said, “Listen, we don’t have to start the drip, we can just give her a bolus and if she’s better, we’ll know we did the right thing.” We gave her the bolus and suddenly she went back to playing. To being a little girl.

BC: The younger kids, if they feel better they still like to play. The little kids don’t realize what they are missing. They are in the here and now. They will throw up and then they want to go into the play room two minutes later.

HH: That kind of resiliency is so beautiful. And it’s not always possible. Part of working as a bedside nurse with critically ill children includes helping patients and their families approach death. Do you think children who are dying can understand what death means?

BC: There are theories about how different age groups understand what death is. Up to about four years old, death is a fairytale. Very young children don’t realize it’s permanent. But, I do feel they have a sense they are leaving. They sense they are going somewhere different from where they are. If their parents have spiritual beliefs, they might say, it’s OK you’re leaving, you’ll be able to play or run, or be with angels or Allah or whatever is most comforting for that child. The older kids often know; they have accepted it. You’ll see them wait until it feels right. I’ve seen so many patients who’ve waited until there was a sense that their family would be ok, that their parents were ready or everyone was gathered. It’s very beautiful how that happens.

HH: Within a medical setting, how do you help patients and their families navigate a deeply private, personal event? Do rules and procedures ever conflict with the patients’ or families’ wishes? What can you do to respect those wishes?

BC: If a child is dying on the unit, nurses will stop at nothing to grant their wish. We’ll go through many, many hoops. We have helped patients go outside to feel the sunshine, or played their favorite song or music, or found their favorite movie. Sometimes a patient will want to do something that takes a great deal of coordination or effort or thinking outside the box and some staff might say, “That’s impossible.” And you just have to say, “Ok, well, but we have to think of a way to do it.” You have to gather a band to make it happen. The bedside nurse is usually the one to see that and to get others on board — it’s almost impossible but it can still happen.

HH: When you do lose a child, are there ways in which you can continue to support the family?

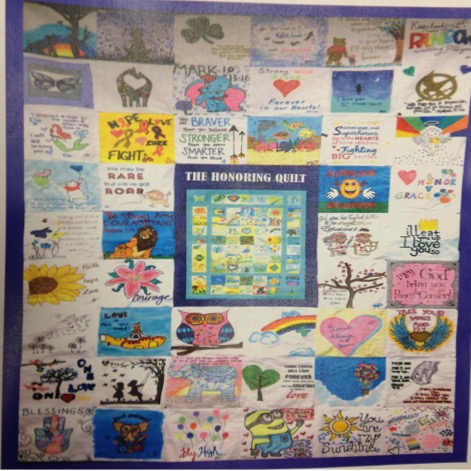

BC: In the immediate moment, when a child does pass, we try to make that experience for the family as human as it can be. One thing we’ve done is so small, but it’s made a big difference. After a child dies, they have to travel to the morgue. They used to be taken there on what’s called a morgue gurney, which is ugly, gray plastic. We’d tell patients and families to leave the hall so they wouldn’t see. I wanted a way for patients who died to leave their rooms without feeling like we were hiding them, or disrespecting them with this gurney.

Our social worker offered an idea she’d heard about, how in some places they cover the gurney with a quilt. Every nurse on our unit contributed a square and we made the quilt. Now, we cover the gurney with this quilt and we don’t ask people to leave the hall. We’re not trying to hide the fact of death—but to make it human. That blanket is like a celebration of the patient’s life.

It’s a blanket of love we cover the child with as they leave. Each square has a saying or an image chosen by one of our nurses.

HH: What does your square say?

BC: All You Need Is Love.

HH: How do you live with the pain of helping a young person die on his own terms, or looking into the face of toddler who is suffering, and still stay functional? Still do your job?

BC: Well, you sort of have to stay functional. Right. It’s the same for parents as for nurses. Before my kids were grown, I’d go home from work and be comforted by the chaos. I had four boys, doing everything boys do! And my husband Joe was working as well. It was laundry, cooking, homework, going to school meetings. I didn’t have time to think about what I’d been through at work. If I did, I would try to think of fun things to bridge home and work. Like if my kids were making Valentine’s cards for school, I’d make little Valentine’s mailboxes for our unit. Or bake gingerbread houses—I would. My house was so chaotic I was glad to go to work and get a break. Now that my kids are older, and my last one has left, I think more about work when I’m home.

HH: Part of your work is witnessing the loss. When that happens, what do you do to make yourself ok enough to walk into the next room and help that child trying to heal?

BC: That is really hard. Your heart feels like it weighs a million tons. It’s hard for me to go into the next room and smile and be happy with someone after caring for a child who is sick, or dying. But some nurses feel better seeing the patient next door, who is healing. And we all respond in different ways to caring for someone who passes; some nurses want to go home and be quiet and think. And others want to stay at work because they don’t want to be alone. I tell the young nurses on our unit, “Hold your pain close.” Thich Nhat Hanh says, “If you don’t know suffering, how can you be happy?” Your suffering can turn into happiness. Instead of pushing it away, hold your pain close, like you would a puppy that’s crying, until it can become a part of you.

HH: That’s so beautiful, the idea that pain can become an integrated part of you.

BC: It is a part of you. It never leaves.

HH: I once asked you if you remembered all children you’ve worked with over the years, and you said something like, they’re all in me.

BC: They are, they are all with me. We do this thing on the unit now—I don’t think we were doing it yet when you were there. We make a button with every child’s face and the nurse who cares for them wears their button. Recently I got out all my buttons and I had over 200. I remember every one of them. Maybe not their name, but I know who they are.

HH: You’ve been on the transplant unit, 5200, for 15 years. That’s unique, and it’s the exception instead of the rule. Right? Can you say why—when so many nurses move on from that unit—you’ve stayed?

BC: You asked me before how the culture of nursing has changed in the decades I’ve been doing it. The leadership of nursing is always trying to prove something, about nursing. Not that we’re as good as doctors but that we’re valuable. A lot of nurses are encouraged to continue their education. To get a master’s degree and be a nurse practitioner or get a PhD and teach. It’s good to encourage people to advance, but it can also make people at the bedside feel like, “Oh maybe I should just do this for a year or two and go back to school.” But for me, nursing at the bedside, that’s where it’s at. That is where healing happens. So, I wish management would put more emphasis on how important bedside nursing is vs. furthering your education. I’ve taken so many classes and certifications programs that have helped me at the bedside, but I don’t feel like I need to move on. One young nurse on our unit said to me, “I don’t want to go back to school. I want to stay at the bedside. What’s wrong with me?” And I said, “There’s nothing wrong!”

HH: Last question Bobbie. What do you do to relax or take care of yourself so that you can stay so caring and capable at the bedside?

BC: I’ll tell you what, I get in my lawn chair and I go look at the stars at night, in my backyard. I do have a telescope but I have a hard time using it. When I can figure it out, I look at Saturn, its rings. Or if I can’t be bothered with the telescope, I just get out my binoculars and lay in my lounge chair and look up at the stars.